Vitamin D Regulation

By Jens Allmer

Calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D, is a powerful hormone that needs tight regulation in the body. It acts like a “key” that fits into specific “locks” (receptors) to manage important functions like calcium and phosphate balance. Too much or too little can cause harm, so the body carefully controls how much is made.

The body converts stored vitamin D (Calcifediol) into Calcitriol in the kidneys, but if Calcitriol levels get too high, enzymes slow down its production and break it down. Calcium and phosphate levels in the blood also help regulate this process.

Low calcium triggers the production of more Calcitriol, while high calcium or phosphate slows it down. Additionally, low phosphate increases Calcitriol, while high phosphate decreases it. These processes work together to maintain balance, ensuring proper calcium and phosphate levels in the blood.

If vitamin D stores are low, the body can’t produce enough Calcitriol, which can lead to health problems.

For more technical details, read on.

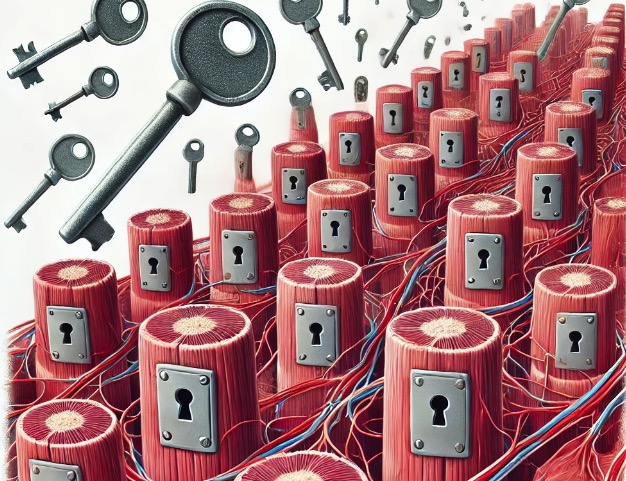

A potent hormone like Calcitriol (see Vitamin D3 disambiguation), needs to be under tight control. Otherwise, there is a potential for physical harm. A hormone alone is quite useless. It would be like a key without a lock. While modern humans tend to collect keys for which they forget where the locks are, the healthy human body has appropriate locks for all the hormones it produces.

An example could be the insulin hormone, which turns the glucose lock, allowing cells to absorb sugar from the bloodstream and use it for energy. However, when this system malfunctions, it leads to two distinct types of diabetes (Type I and II).

In Type 1 diabetes, the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, so there is less keys available and with less keys, less glucose enters the cells.

In Type 2 diabetes, the body still produces the key (insulin), but the cells become resistant to its effects. Either the lock doesn’t work properly any more or we just have less doors and therefore less locks so that less sugar can enter the cells. Both mechanisms lead to elevated blood sugar levels with all the detrimental effects.

Overall, we can imagine that many keys turn many locks on many doors in many cells. The following is what ChatGPT was able to produce. Obviously, the keys should be circulating in the blood and the locks should be on doors which could be opened with the keys. Clearly, all keys of one type (e.g., Calcitriol) must be identical and the locks (receptors) must be identical for this to work.

Keys and locks like hormones and receptors.

Keys and locks like hormones and receptors.

To prevent such problems as diabetes, the human body developed mechanisms to control the amount of any hormone (Type I). Another route would be to reduce the amount of receptors for the hormones (Type II). There is a third mode of action (not in the image). When co-factors are involved, the effectiveness of a hormone binding a receptor can be modulated, or the receptiveness of the lock for the key can be modulated. An example would be magnesium (Mg) for the binding of Calcitriol to the VDR receptor. For the lock and key example, we could imagine oil and glue to modulate the effectiveness of the system.

Typically, the number of keys is modulated, and only in chronic disease or drug abuse is the number of locks modulated (diabetes Type II). Another example is drugs of abuse, which work well in the beginning but lose their effectiveness over time. The attempt to increase the amount of keys (drug) only works temporarily, and a vicious cycle starts.

Calcitriol is the key that turns the vitamin D receptor (VDR). The effectiveness of the system is enhanced with proper amount of magnesium (a mineral that we are often deficient in). We often think that when we want to achieve something, we just have to put more effort into it (produce more keys). For hormones, the relationship is slightly different.

/images/hormoneresponse.png]] Typical hormone response curve.

Most hormones have a sigmoidal response curve, as seen in the image above. There is an amount of hormone, that has little to no effect (0-40) then there is a small amount of hormone change that has strong response (40-80) and then no matter how much hormone we add, there is no more effect (>80). The figure is not perfect in the scientific sense since each hormone would have different concentration levels, and the units are not given. I hope it is enough to make clear that there is a range where the hormone is very active and regions where it is not. Compare this to the levels of Calcifediol in the blood. Calcifediol is not Calcitriol and, therefore, not active, but the healthy human body can produce Calcitriol from Calcifediol. Therefore, the Calcifediol stores are important to monitor.

Now we established, that the level of the hormone is regulated in the normal case and that the receptors stay relatively constant. We also established that if either of them is compromised, the system does not work properly anymore. Thirdly, co-factors can have some influence. Translated to vitamin D, this means that the amount of receptors is constant. There are some diseases that occur due to insufficient amount of receptors, but the amount of VDR is typically not downregulated due to excessive availability of Calcitriol, so there is no effect similar to drugs of abuse. Magnesium is a co-factor of the binding process of Calcitriol to VDR and enhances this binding. Finally, the amount of Calcitriol is under tight control.

Calcitriol Control?

How exactly is Calcitriol (active vitamin D) controlled? Calcifediol (the storage D3) is converted to Calcitriol in the kidney. The conversion is performed by 1α-hydroxylase.

Calcifediol —kidney(1α-hydroxylase)—> Calcitriol [1]

25-(OH) Vit. D3 —kidney(1α-hydroxylase)—> 1,25-(OH)2 Vit. D3 [2]

Here it might make sense when we use one of the synonyms. We see in the second reaction, that the hydroxylation (adding OH) in position 1 is what is performed by 1α-hydroxylase. First, there was one OH at position 25 (Calcifediol), and after, there were two in positions 1 and 25 (Calcitriol). This is not much of a regulation, of course. Now, high levels of Calcitriol inhibit 1α-hydroxylase and promote another enzyme: 24-hydroxylase.

Calcitriol (high levels) —–| 1α-hydroxylase [3]

Calcitriol —kidney(24-hydroxylase)—> 1,24,25-(OH)3 Vit. D3 [4]

Calcium, phosphate (high levels) —activate—> 24-hydroxylase [5]

Calcitriol (high levels) —activate—> 24-hydroxylase [6]

This new molecule (Calcitetrol) is less active than Calcitriol, especially in terms of calcium homeostasis. However, it has not yet been completely deactivated. Calcitetrol is further modified until it becomes Calcitroic acid and is discharged via the kidney. We will not consider the molecular details here unless they become important at a later point. For now, we know that high Calcitriol levels reduce the efficiency of reaction 1 by inhibiting the enzyme 1α-hydroxylase (reaction 3). High calcium and phosphate levels, on the other hand, activate (make it more efficient or increase the amount) 24-hydroxylase, which reduces the amount of Calcitriol. The activation of 24-hydroxylase due to high Calcitriol levels (reaction 6) is a negative feedback loop that ensures that the levels of Calcitriol are in check.

Above we considered the deactivation of Calcitriol. The parathyroid cells have calcium sensing receptors and can thereby determine the amount of calcium in the blood. Low levels of calcium stimulate the release of parathyroid hormone (PTH) that is responsible for the activation of 1α-hydroxylase which increases the rate of conversion of Calcifediol to Calcitriol (reaction 2).

parathyroid hormone —activates—> 1α-hydroxylase [7]

Calcitriol —inhibits—| PTH production [8]

Regardless of whether there is enough calcium in the blood or not, Calcitriol inhibits the further production of PTH. So if blood calcium is low, PTH is excreted, leading to more Calcitriol (reaction 7), which inhibits PTH (reaction 8). This fine-tunes the amount of calcium that is in the blood (there are more mechanisms, though), which must be maintained with very small errors (too much and too little are highly detrimental to our health).

Calcium levels are critical and need to be maintained precisely. Phosphate is another molecule that needs to be tightly controlled.

Phosphate (low levels) —activate—> 1α-hydroxylase [9]

FGF23 —inhibits—| 1α-hydroxylase [10]

FGF23 —activates—> 24-hydroxylase [11]

Calcitriol is not only involved in calcium homeostasis but also in phosphate homeostasis. Therefore, low phosphate levels increase the amount of Calcitriol by activating 1α-hydroxylase (reaction 9) which in turn makes reaction 1 more efficient. On the other hand, the Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 (FGF23) is a hormone that is excreted upon high phosphate levels, which inhibits 1α-hydroxylase (reaction 10) and activates 24-hydroxylase (reaction 11). Both decrease the amount of Calcitriol by reducing reaction 1 and by increasing reaction 4.

These are important mechanisms of the regulation of Calcitriol. Keep in mind, though, that if the Calcifediol stores are depleted, there is no way that Calcitriol can be produced. Too little Calcitriol has all kinds of detrimental effects on the human body and manifests itself in various diseases, a topic for another time.